He compares the extant Greek fragments with their Arabic translations and finds that, while the translation is not literal, minor glosses and some rephrasing are used only to render the translation into more idiomatic Arabic in general, the translator took care to preserve Bryson’s original ideas. 6 In his recent translation and commentary on Bryson Arabus, Swain convincingly demonstrates that there is little need for concern about the translator’s accuracy. Martin Plessner has argued that the translator into Arabic epitomised and reordered the work, 5 but Simon Swain has shown that Plessner’s evaluation of the text is not entirely accurate. Since we are dependent on the Arabic translation for the vast majority of the text preserved, the question of the reliability of this translation is key.

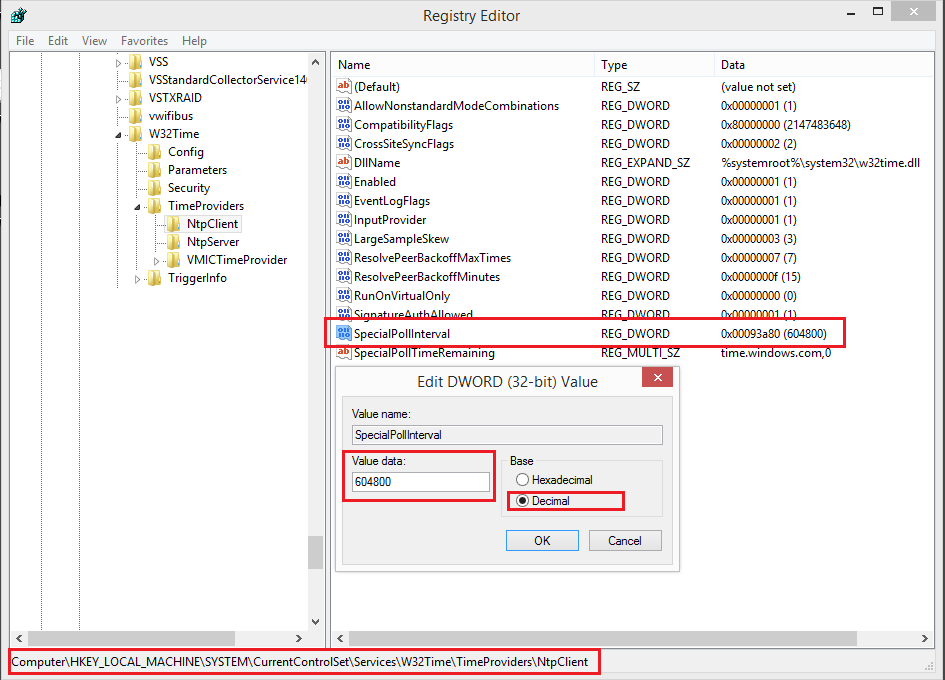

Midico change synchronization full#

Although these two fragments are not much to go on, the treatise also survives in full in Arabic translation, in the manuscript Cairo, MS Dār al-kutub, Akhlāq 290 Taymūr. Stobaeus’ doxographical collection preserves two fragments from Bryson’s Oikonomikos: one describing the chain-like interdependence of crafts and another dealing with slavery in the household. Why was Bryson discussing physiology in a treatise dedicated to household management? How can medicine, a complex expert field of knowledge, be useful in explaining the principles of this seemingly familiar and even mundane area? In this paper, I analyse how Bryson combines the two knowledge domains and, situating the text in his most immediately scientific context, argue that he produces a genuinely unique medico- oikonomic account of human nature. This naturally leads to the question of motivation. A closer look at this Oikonomikos reveals that it is also strikingly unusual: the very beginning of the treatise contains an account of human physiology, while the oikonomikos logos is interwoven with extensive, and often quite technical, medical claims. Furthermore, one of the key arguments in the treatise is the account of inexorable co-dependence of all crafts, a notable contribution to the genre. It presents a discussion of property (its acquisition, preservation and expenditure) and then moves on to the discussion of the proper treatment of one’s servants, wife and (male) child, thus covering all the ground typical of oikonomia. The treatise not only has the standard title it is also structured according to the standard preoccupations of the genre. Bryson’s Oikonomikos is an especially notable example of how the Neopythagoreans adopted this genre. 3 However, the interest in both physiology and oikonomia, household management, 4 is certainly present in their texts too, with some significant precedents in the broader Pythagorean tradition. 2 In general, the Neopythagoreans are known more for their theories of the soul than for those of the body. 1 While the complicated transmission of the text is undoubtedly partly to blame, Bryson discusses topics that are, in general, rarely found together and are not readily associated with the Neopythagorean tradition in particular: household management and human physiology. The Oikonomikos of Bryson, a Neopythagorean philosopher, is a text rarely discussed in the scholarship on ancient philosophy.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)